Inside Tom DeLooza’s Wet Plate Collodion Photography

By Susan Piperato | Spring 2018 | Makers | The Studio

Despite—or maybe because of—digital photography’s ease and convenience, many photographers are turning to antique analog photographic methods, including Tom DeLooza, who practices the Victorian art of wet-plate collodion portraiture at his studio in Kingston’s Midtown Arts District.

“The wet-plate collodion process is experiencing a renaissance in response to the digitization of not only the photo industry, but many art-making practices and parts of our lives,” he says. “People are looking to use actual materials and chemistry to make art, not spend so much time editing on a computer screen. There is some element of adventure as well, as there could be accidents, spills, or characters that come out of having to troubleshoot a problem manually; that doesn’t happen so organically when using digital equipment.”

DeLooza, who grew up in a family of “hands-on folks” in the Finger Lakes region, approaches life with a “from-scratch mentality.” He’s made a career as a wet-plate portraitist since graduating in 2004 from Alfred University, where he studied painting and illustrating. When he started out, he says, there were few wet-plate photographers; now the art is practiced by thousands in the US and Europe thanks to workshops like the ones DeLooza teaches at the Center for Photography at Woodstock and for local school groups.

Invented in 1851, wet-plate collodion photography produces images directly onto glass or metal plates (aka “tintypes”) without a negative. Being portable, inexpensive, and less toxic than its predecessor, the Daguerreotype, the wet-plate allowed photographers to make a living traveling from town to town or later to amusement parks to offer photo sessions. Through the 1930s, families lined up to create haunting, one-of-a-kind portraits of themselves.

Photo by Roy Gumpel.

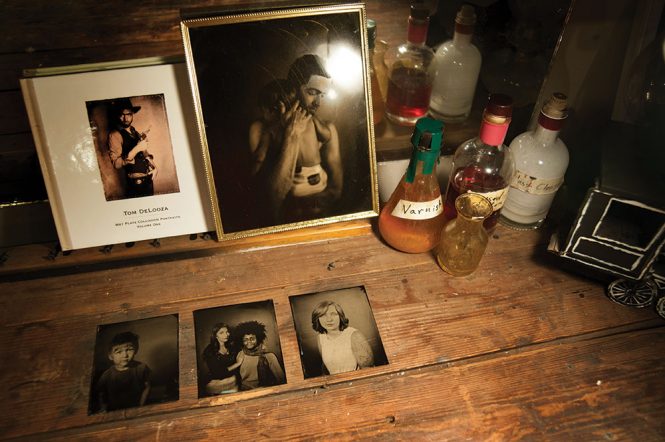

Creating a wet-plate portrait takes about 15 minutes, says DeLooza, who runs a tintype photo booth at events like the annual Hudson Valley Hullaballoo. Before the plate is exposed, it’s washed with collodion, then placed in a silver nitrate bath. After the portrait is taken—in DeLooza’s case, using one of a collection of antique cameras he’s refurbished himself—the plate is developed in the darkroom, washed with water, and fixed. After drying, which DeLooza does over an oil lamp, varnish is applied.

Artists and sitters alike appreciate the process’s slowness. “[It] feeds into the sitter becoming more relaxed and comfortable,” says DeLooza. “You have to really think about what you want to photograph. The time it takes to make an image is time in which to reflect, meditate, get to know people, or fine-tune your still life or setup.”

The resulting images, he notes, “tend to feel more authentic” and “have weight to them, both as an object and visually, as there is much more actual material—silver, chemistry, glass, or metal.” Plus, the “straight-to-plate” process “is only one step removed from nature, as opposed to making a negative, then printing from that negative, or scanning, or computer chips interpreting the light.”

Wet-plate is also easily affordable: DeLooza’s portraits cost $45 for a 4”x5”, $80 for a 5”x7”, and $150 for an 8”x10” portrait. He also offers scanning and printing to create copies of portraits. “I am totally not anti-digital,” he says.

Many of DeLooza’s family and individual clients return for annual portraits on their birthdays or to mark significant personal events, and he even shoots at weddings. What primarily connects him with his clientele, he says, is the desire to pass “something of ourselves on to the next generation”—an ever-pressing need in the face of digitization. “What do we leave in time capsules?” he asks. “Newspaper clippings, photographs, yo-yos, toys, letters—real things. What will the time capsules of tomorrow contain? A piece of paper with an Apple ID and a cloud password?

“People who get their portraits done are looking to see how that translates through the use of the process,” he says. “Perhaps they feel a bit of a connection to the past and/or loved ones they have seen in tintypes or [portrayed] using similar cameras to mine. They are also looking to have a keepsake. I like the idea of bringing back the occasion of having your portrait made.”

Photo by Roy Gumpel.