Wright at Home: Dragon Rock at Manitoga

By Joan Vos MacDonald | Spring 2022 | Design Feature

Sparks must have flown when Russel Wright met Mary Small Einstein at Woodstock’s Maverick Festival in August of 1927. The couple eloped only a month later. The festival’s woodland setting also engendered a lifelong love of the Hudson Valley and would later inspire the design of the couple’s iconic home, Dragon Rock.

Photographs of the festival, a regular fundraiser for Woodstock’s Maverick Art Colony, evoke the woodland revelry of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The festival was attended by thousands of visitors, who often arrived in fanciful costumes and felt free to celebrate in unconventional ways.

“Dionysian” is the word Jennifer Golub, author of Russel and Mary Wright: Dragon Rock at Manitoga (Princeton Architectural Press, 2021), uses to describe the festivities. “I think it was a celebratory space of inclusion, of free play, where the creative spirit could really flourish,” says Golub. “And I think Russel and Mary were both artists who came from very uptight families and they were being groomed for lives that didn’t feel authentic to them.”

Russel, who would become one of America’s foremost industrial designers, produced events for the festival’s Quarry Amphitheater, performances set in an abandoned bluestone quarry with planks for seating. Mary, a designer, sculptor, and businesswoman, attended the festival with avant-garde artist Alexander Archipenko. Mary was raised to be a debutante and Russel’s family wanted him to be a lawyer, but neither was interested in a conventional life.

Mary and Russel Wright, photo for The Guide to Easier Living, 1950. (Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center.)

After marrying, the couple formed Wright Accessories, a successful home accessories design business. Russel is best known for his American Modern design, the most widely sold American ceramic dinnerware in history, designed for Steubenville Pottery, as well as his American Modern flatware designs for John Hull Cutlers Corporation. The furniture, dining accessories, lamps, glassware, rugs, and textiles he designed were instrumental in encouraging Americans to embrace Modernism in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.

Not only did Russel’s designs become popular but the couple influenced the lifestyle decisions of a generation with their best-selling book, Guide to Easier Living (1950), which describes efficient home design and management while rejecting the confines of conventional gender roles and class. In addition, Mary founded America Designs Inc., an organization that supported the works of American industrial designers.

Dragon Rock at Manitoga

A Little Woodstock in Garrison

The Wrights’ love of Hudson Valley landscapes eventually led them to buy a 77-acre plot in Garrison. They named it Manitoga, after the Wappinger tribe’s word for “great spirit.” The site was an abandoned quarry, reminiscent of the Woodstock site where they first met.

“They fell in love with that part of the world and felt an affinity with nature, that particular landscape,” says Golub.

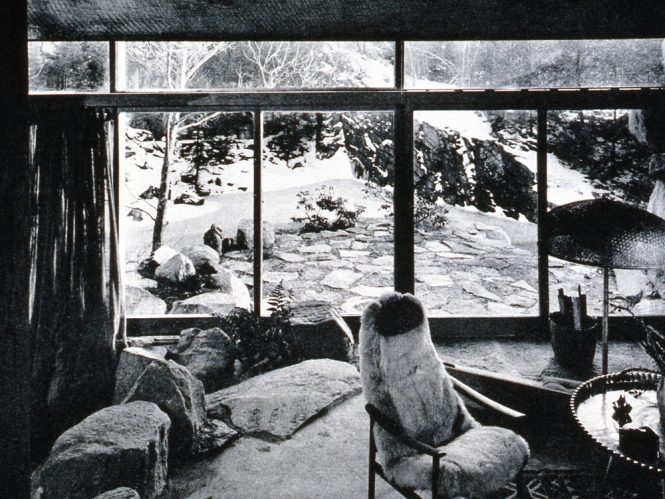

Dragon Rock, Life magazine, c.1962 (Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center.)

Russel and Mary were very much partners in both the design business and the vision for their Manitoga home, a fact Golub says may be overlooked when Russel Wright’s work is lauded. “Women at that time were not to be architects,” says Golub. “They were not to be designers and they expected to take secondary roles behind men. That doesn’t take anything away from Russel. He was a formidable designer and Mary obviously recognized the enormity of his talent, but she played a very large role in identifying and developing the site. Very sadly, she passed away before the home was built. It’s actually Russel himself, who in her obituary and in lectures, goes to great lengths to ensure she’s acknowledged and how much authorship she had in the development of the home. I felt it was my duty to bring that to light.”

A Celebration of the Natural World

When they purchased the property, the quarry was filled with rubble and the surrounding site thickly forested. Stones cleared out from the quarry were used in Dragon Rock’s construction. Boulders were moved to support the house, while rocks from the site were used inside, serving as walls, fireplace surrounds, and flooring materials. A tree from the property provides a ceiling beam support.

“It’s designed in full appreciation of that natural world,” says Golub.

Perched on a quarry bluff, Dragon Rock is situated for the best possible views of the surrounding wilderness. A glass facade makes the most of those views, particularly a waterfall which pools below, as well as the rolling forested hills beyond. The home’s interior reflects the colors and textures of the surrounding forest—warm browns, vernal greens, and the pale white of winter—with hemlock needles pressed into plaster walls and butterflies seemingly floating within acrylic panels.

“I almost feel like the garden was designed as rooms and the house was just another room, an enclosed room,” says Golub. “It’s just one more station in the sequence of outdoor rooms, so it’s absolutely a celebration of the natural world.”

After Mary died in 1952, Russel eventually moved to Manitoga full time, so he could spend more time with his daughter. “Annie was only two when Mary passed away,” says Golub. “He lost his wife, he lost his best friend, he lost the mother of his child, his partner, his business practice. The guy really had a very difficult transition. Then I think Russel came out on the other side of this and said, ‘Okay, I am pulling through this my way.’”

Martha Graham Girls, a landscaped grove of gray birch trees that move like modern dancers in the wind, c.1980 (Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center.)

He eventually completed the home’s construction with the help of architect David Leavitt and, until his own passing in 1976, Russel shaped, repaired, and reclaimed the surrounding woods, taking on an unparalleled feat of landscaping and conservation.

“That became Russel’s labor of love for the last 20 years of his life,” says Golub. “From the time he closed the design firm, after Mary’s passing, and he relocated to Dragon Rock full time, that was his fascination.”

Home as Theater

Golub’s book describes the care with which Russell executed his stewardship of the land. He dammed the quarry to create a swimming hole and rerouted a stream to create a waterfall. He removed vegetation to reveal distinctive boulders, pruned branches of stately hemlocks, and created sequenced spaces reminiscent of a Japanese villa garden. He installed simple bridges and carved out meadows. He cleared trees along the trails originally created by the Native Americans who once hunted in the area.

Golub sees the house and grounds as Russel’s defining production, “live theater on a massive scale,” and his care of the woodlands with its hemlocks, mountain laurel, dogwood, black huckleberry, and lowbush blueberry as a pioneering blueprint for environmental practices.

Residential divided vegetable bowl, Melmac, c.1953

(Russel Wright Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.)

“What was beautiful was that Russel developed a sustainable practice,” she says. “He didn’t import anything foreign. He worked very strictly within what was indigenous and natural to the site. It was more like being a land steward. He knew his property well. He celebrated it and worked to enhance it.”

Manitoga was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006. It is one of the few 20th-century modern homes with an original landscape that is open to the public.

Golub was so impressed by her first visit to Manitoga that she felt compelled to write about it. She had already written a book about modernist architect Albert Frey after discovering how little was written about his work. “It was a very similar feeling when I arrived at the grounds of Manitoga, before even arriving at the home, because the property was so spectacular,” says Golub. “And highly referential to Japanese gardens. The central water feature, the way the landscape reveals in certain places and conceals in others, and the different textures underfoot as you approach, are all very intentional while being very natural. I never experienced anything like it, other than the imperial villas in Kyoto.”

Serving pieces: Spun aluminum, bamboo, birch, and cork, 1933 (Wright Auctions of Art and Design)

Upon visiting the home she learned that the last publication about Russel Wright’s work was an exhibition catalog for a 2001 show at the Cooper Hewitt. It was long out of print. “There’s a whole generation of people for whom there is literally nothing in print about one of the seminal designers of the United States,” says Golub. “Appreciating that there needed to be an inquiry into Mary and what her participatory role was, I felt like I was answering a call. It wasn’t something I set out to do. It was something that compelled me.”

Golub hopes that her book prompts readers to visit the site and that the beauty of the site stirs their spirits.

Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center celebrates the Wrights’ design philosophy and work through tours, programs, events, and free year-round access to woodland trails. “They are really looking at programming to keep the site energized and fresh,” says Golub. “It’s such a jewel for the community. It should be a real source of pride.”