A Geothermal Greenhouse Grows Microgreens All Year

Tongore Brooke Farm Plants the Seed for An Agricultural Revolution in the Northeast

By Marie Doyon | Photos by Deborah DeGraffenreid | Winter 2017 | Farm & Garden

It’s been a tough year for farming across the country. While drought and forest fires destroyed crops in California, Hudson Valley farmers lost many fruits and vegetables at harvest due to an extremely wet spring.

But pioneering environmental architect Michael McDonough has a plan that could not only insulate growers from the whims of Mother Nature, but also create thousands of jobs. His enterprise, Tongore Brook Farm, located on his 30-acre property in Stone Ridge, is the prototype.

Architect-turned-farmer Michael McDonough harvesting organic microgreens.

The farm is housed within an 18-feet-tall, 3,000-square-foot greenhouse near McDonough’s home on a heavily wooded, rocky Catskills slope, 900 feet above sea level—not the most viable site for an intensive agricultural venture. But this four-season greenhouse is a feat of engineering: It runs on 10 percent of the energy of a conventional facility and can produce 25,000 to 30,000 pounds annually. After three years of crop testing by experienced growers, McDonough took over the growing in 2016 and began producing certified-organic microgreens and specialty crops for chefs and local grocery stores. Tongore Brook Farm’s microgreens are sold at local Hannaford and ShopRite stores, Emmanuel’s Marketplace in Stone Ridge, Peter’s Market in Napanoch, Adam’s Fairacre Farms, and Mother Earth’s Storehouse in Kingston.

Tongore Brook Farm’s 3,000-square-foot geothermal greenhouse.

“Greenhouses of this sort would normally get to 140 degrees or higher [in the summer], which would make it virtually impossible to run them, unless you put a lot of energy into it—big, big air conditioners, big fans,” says McDonough, a longtime Ulster County resident whose practice is based in New York City. “Cooling and, in particular, dehumidification, takes four times more energy on average than heating. So, in the summer, that gets to be problematic.” Humidity is not only expensive to control but also dangerous for plants, he explains, as too much moisture causes disease.

The majority of cooling systems, from AC units to refrigerators, rely on compressors, which use a tremendous amount of energy. Determined to avoid the cost and negative environmental impact of using a standard cooling system, McDonough, a self-taught engineer, decided to invent something new. In 2006, he applied for a grant from the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA) to develop a compressor-less system for cooling and dehumidification.

The magic of McDonough’s system is housed in a small, hangar-like building that sits near the greenhouse between two well caps. This little building’s roof supports a 1,200-square-foot solar array that enables Tongore Brook Farm to run a net-zero energy operation. The outbuilding also houses McDonough’s proprietary tech cluster.

Inside the hangar, a panel of PVC and copper pipes, filters, valves, and meters takes up an entire wall. In the middle of the near-symmetrical arrangement is a small, inconspicuous metal box—the plate heat exchanger.

At the heart of the two-stage, closed-loop system is a basic law of physics: hot goes to cold. Cold water passes through coils in the greenhouse floor, which pulls heat out of the air. After circulating, the warmed water passes into the hangar, transferring its heat load to cold groundwater through the exchanger, and then returns, cooled, to the greenhouse. Only on the hottest days of the year does a high-efficiency backup compressor kick in to cool the groundwater a few extra degrees.

The greenhouse system has taken layer after layer of tweaking. “I have always tried to innovate in all the [areas] I’ve worked in,” McDonough says. “I had to learn plant science and biology and soil microbiology and composting microbiology because I have to understand the temperature and impact of all the different processes.”

With quickly producing microgreens, McDonough can turn a square foot of greenhouse space around in less than a week, meaning each of the 20 beds has the capacity to generate up to $25,000 worth of produce a year. And if McDonough installed two-level beds—which he calls “a modest vertical farming methodology”—he could increase his yield by 50 percent.

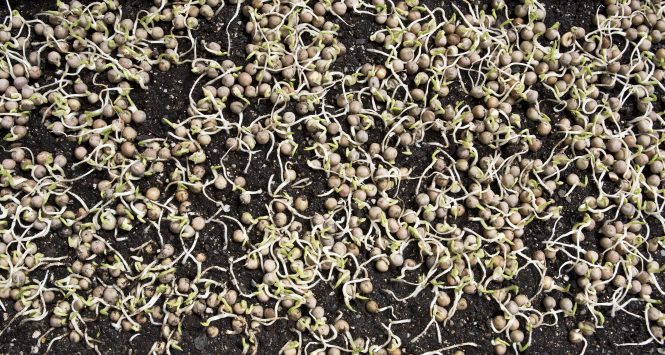

The finished product

While the initial setup costs for a facility like McDonough’s are steep, the potential return could be a huge stimulus for the region’s economy. “The big-picture goal is to develop four-season farming for the Northeast to provide year-round food and jobs,” McDonough says—and not just jobs for farmers, but also engineering and tech positions for building and maintaining microgreen-growing facilities.

To that end, he is pursuing both private equity and community-based funding to develop a commercial greenhouse in the Kingston area that would use the same technology as Tongore Brook Farm but on a much larger scale. McDonough’s envisioned 30,000-square-foot facility could create 10 to 20 year-round jobs, with the potential to gross around $5 million per year. Although the project’s details are still under wraps, he hopes to see the facility open within the next two years. If all goes well, this next greenhouse may mark the start of a new chapter of the region’s agricultural legacy.