Staging a Comeback: The Stissing Center

By Jamie Larson | Paul Clemence | Winter 2019 | The Room

With the amount of attention that it’s getting these days, it’s hard to believe the Stissing Center sat abandoned for 30 years. Originally built as the memorial hall for the town of Pine Plains in 1915, the building has had several lives. Initially, it served as a meeting hall and performance space, before being used as an office building, a movie theater, and finally a laundromat. But by the 1990s, the large, brick, iron-framed building, with its tall windows and many-gabled roof, was empty, and came to be considered a bit of an albatross.

In 2014, to save it from demolition, local resident Jack Banning spearheaded the Pine Plains Memorial Hall’s purchase from the town of Pine Plains. One of the first calls he made, while reckoning with his decision, was to Doug Larson, director of architecture and design at Larson Architecture Works, and a part-time resident of Pine Plains, asking his opinion. Banning was surprised when Larson volunteered to design and oversee the restoration for free.

Photo by Paul Clemence

“Jack asked me to look at it, and one thing lead to another,” says Larson. “These small towns have a legacy, but towns with empty lots are on their way to oblivion.”

The revitalization of the entire structure will take a few more years, but the main piece of the project, the central performance hall, is mostly finished, and last summer and fall the space hosted the Construction Concert Series, a lineup of fundraising performances that included an evening with Winton Marsalis. The goal for the building, according to Banning, is to use it to draw people to Pine Plains and boost its economy, effectively putting the town back on the map, and the restoration project has become a way for many affluent second-homeowners to support the town philanthropically. The renovated hall will be used to present high-quality musical and theatrical performances onstage, as well as to host community events.

Photo by Paul Clemence

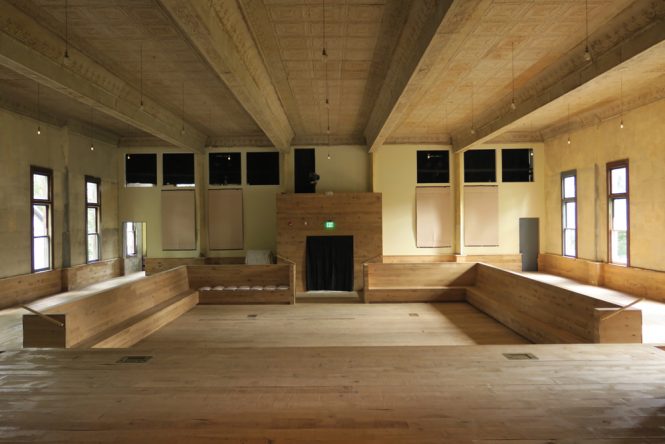

The center’s design harkens back to the era of agrarian meeting halls. It’s a warm and welcoming space, with banks of tall, slender windows along the walls pulling in the light from the surrounding tree-lined grounds. The abundance of natural light makes the new, raw oak floors glow, giving the space a folksy ambiance.

Larson’s design is conducive to a wide variety of gatherings and activities. As such, it integrates crisp modern lines with the building’s preexisting rustic elements. Most striking is the preserved but purposefully unrestored ornate tin ceiling. Its finely detailed pattern is showcased by a rusty patina. The hall’s original exposed brick and weathered plaster have also been retained where appropriate. The harder edges of the new elements enhance the antique elements of the original ceiling and walls through contrast.

Photo by Paul Clemence

While the building is culturally significant, Larson says it was no masterpiece of craft, so he and the center’s new board declined to pursue a state historic designation. That decision has allowed greater freedom to add contemporary elements. “It really was a big brick fortress,” says Larson. “It was just a 60-foot-by-50-foot room with a flat floor. It was a little formless, to be honest. I tried to figure out a design that better connected the building to the town.”

Larson decided to rebuild the hall on two levels, with a raised perimeter and a larger, recessed open floor surrounded by a low interior wall lined with built-in bench seating. This “box within a box” design is highly sculptural and is all made of the same light, unfinished, skip-planed white oak from Pine Plains-based reclaimed lumber specialists the Hudson Company. The plan “gives you better sight lines and makes the floor more intimate,” Larson says. Aside from the perimeter bench seating, there is no permanent furniture in the space, allowing the hall’s concentric geometry to stand out.

The central stage, made of the same unfinished, white oak, appears to swoop up and flow unbroken beneath the performers toward the deep red exposed brick of the stage’s back wall.

The central stage, made of the same unfinished, white oak, appears to swoop up and flow unbroken beneath the performers toward the deep red exposed brick of the stage’s back wall.

The most controversial part of the design is the stage’s proscenium, or rather its lack thereof. It’s just a rectangular hole cut out of the wall, without molding. Although the proscenium may appear unfinished, the intention behind it, Larson says, is to communicate that the stage is no more important than any other space in the hall. The original proscenium, which was simply painted on flat plaster, had crumbled. “With the new design, the old arch wasn’t appropriate,” Larson says.

Reactions to the hall’s unconventional redesign have been positive, says Brian Keeler, the Stissing Center’s new executive director. What Larson accomplished, he notes, was to take the community’s hopes for the center’s future and make them real. “I saw the design when it was just a concept, and you could see how it would work,” Keeler says. “But with a performing arts space, there’s also a feel to the room that goes beyond design. This space, especially during a performance, feels friendly and inviting and alive.”