Upward Spiral

A couple designs a spiral house to inform the spirit.

By Carl Van Brunt | Phil Mansfield | Winter 2019 | Features

When Patty Livingston asked her husband, sculptor and painter Tom Gottsleben, to design a guest house for their 35-acre property outside Saugerties, he hesitated. Although he wanted to please his wife, who was also his creative muse, he was not interested in designing a traditional house. But as he began to incorporate bigger spirals in his sculptures, and studied Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s marble sculpture Slide Mantra, he wondered whether he could create a spiral big enough to live in. One day, Gottsleben announced he had come up with a guest-house concept. Inspired by sacred geometry, the idea was for a spirally ascending, multi-story structure. Livingston liked the idea, but felt compelled to ask practical questions like, “Where do you put a sofa against a curved wall?”

Undaunted, Gottsleben created a series of models for the house. The house design was completed in the spring of 1997 and construction on the five-story, 4,000-square-foot building began that December. The Spiral House’s cylindrical walls were built using 52 flat panels—a structural adjustment that answered the sofa question and eliminated the need for curved windows and cabinets. Ultimately, says Livingston, her pragmatism married Gottsleben’s spiritual aspirations to create a design for a curving structure of bluestone, steel, and concrete that met the needs of daily life while allowing its inhabitants to experience a sense of timelessness. The couple liked the result so much that they moved in, leaving their ranch house for guests.

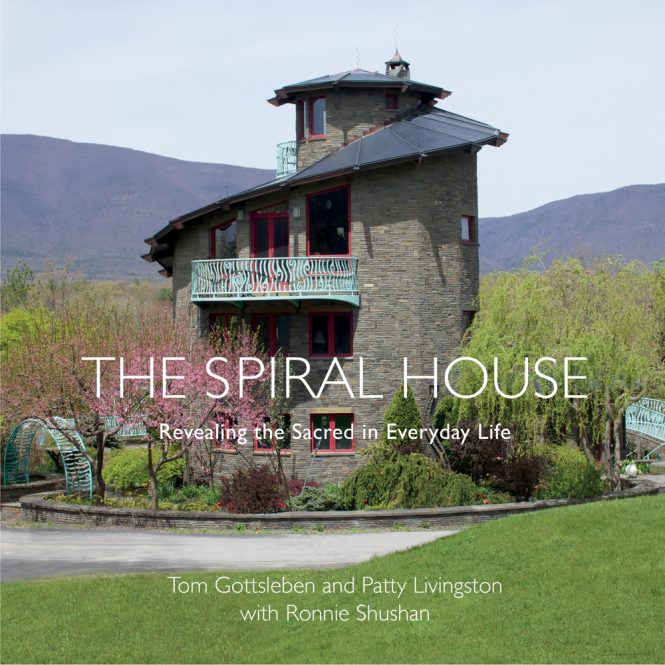

The story of the house’s design and construction has filled a 300-page book, The Spiral House: Revealing the Sacred in Everyday Life (Glitterati Editions, 2019), cowritten by Livingston and Gottsleben, who died in January 2019, with Ronnie Shushan, and featuring photographs by Mick Hales. The book contains chapters devoted to the Spiral House’s inspiration, design, and construction; the nature and energies of stone; Gottesblen’s art; sacred geometry; spiritual journeying; and what it’s like living inside a spiral.

Sacred geometry is an ancient belief that numbers and forms have philosophical meaning, and that built forms are a way to reenact the original creation of order from chaos. All spiritual practices still make use of sacred geometry to better apprehend the divine holistic design of the cosmos and to create religious buildings. Sacred geometry’s roots lie in the study of nature, where mathematical principles can be observed, most famously in the chambered nautilus shell, which grows in a logarithmic spiral without changing shape. The Spiral House’s design, says Livingston, was conceived to “[liberate] the spiral to be what it is: a single, continuous flowing form, with the organic unity of the nautilus shell.”

A drone shot from overhead reveals its copper-clad roof, along with the house’s structural replication of the nautilus shell.

Gottsleben, whose spiritual seeking began as a youth with his discovery of Indian sages Ramana Maharshi and Prem Rawat, was introduced to sacred geometry when a visitor loaned him the book The Secrets of Ancient Geometry & Its Use by Tons Brunés, a Danish engineer and Freemason.

Livingston says she and Gottsleben planned the Spiral House together, working from Gottsleben’s belief that “a built environment can affect our experience, our feelings, and our consciousness.” Livingston, who describes herself as “not much of a seeker,” kept the couple grounded. “I just couldn’t embrace a form, regardless of how beautiful or inspiring,” she recalls, “if it was going to be difficult to live in.” Yet Gottsleben also kept them looking “at the bigger picture,” she admits.

The property lies on a hard bluestone vein that was quarried in the late 19th century. Since the late 1980s, Gottsleben had been gathering pieces from the quarrymen’s scrap mounds of bluestone to repurpose for his sculpture business, Rafferty Rocks, and for landscaping. The grounds are replete with his bluestone works in the form of numerous sculptures, curving and/or stepped walls, walkways, fountains, arches, pyramids, and a terraced pond that fills the former quarry. Building Rafferty’s Bench, a sculptural memorial nestled in foliage that was built for the couple’s beloved Airedale, who died in 1988, marked Gottsleben’s move from painting to sculpture, beginning what Livingston calls “his dialog with stone.” So it was only natural, when it came time to design the Spiral House, that he should turn to bluestone again.

The property’s stone walls, which were built over a 25-year period, follow the hillside’s natural contour, so they appear to rise from the land rather than being imposed on it.

Contractor Herb Silander spent seven months refining Gottsleben’s plans, solidifying his concepts into architectural blueprints. He proposed the Blue Maxx wall-forming system, which uses polystyrene blocks for pouring concrete walls reinforced by rebar, for the basement. Then North Engineers suggested using this system to create a unified wall structure for the entire house, allowing for many windows and cantilevered balconies trimmed with pale blue iron railings.

Situated at the top of a long driveway, the Spiral House resembles a wizard’s castle upon first glimpse, given its spiraling 40-foot form; stone veneer; decorative balconies; and copper-covered roof, which culminates in an octagonal skylight and is topped by a spiraling chimney and several spiraling lightning rods.

The house is built on a hillside, oriented to the mountains in the west, and lacks a conventional front and back. On the western side is the basement, a wide, 2,000-square-foot rectangular space housing an office/work-crew room, media room, and bathroom. The space is accessed through a retractable, multipaned glass door or twin entryways tucked into arched bluestone alcoves on either side. Rising above the alcove entrances are twin bluestone staircases leading up to a second, smaller terrace, accessed via a door between the first-floor living and dining areas.

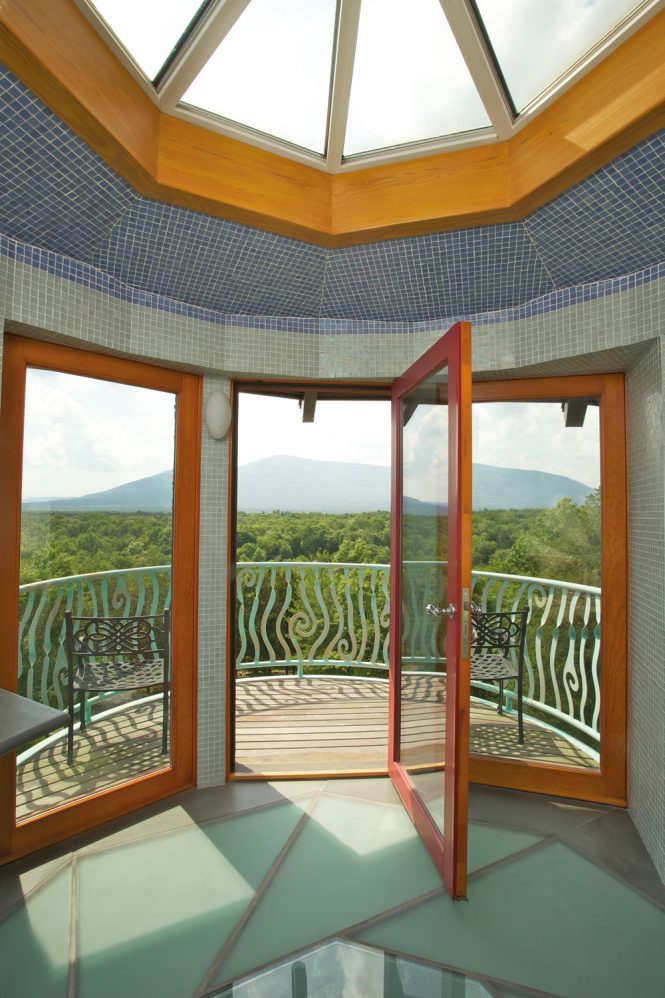

The view of the Catskills from the observation room.

Because “everything about the spiral house is asymmetrical,” Gottsleben writes, he took special care to create a sense of balance. The house is surrounded by bluestone walls, paths, and terraces, along with lush gardens in the warmer months. On the western side, bluestone walls stretch out from either side of the building. On the south side is a “moon garden,” designed for meditation, with inward curving walls and a Buddha; on the north side is a “sun garden” and a large metal sculpture of the Hindu god Shiva Nataraja, the creator/destroyer god, chosen by Gottsleben as the “house deity.” The four-armed god is shown dancing atop a demon within a ring of fire. (Gottsleben and Livingston purchased the piece from an Asian importer. )

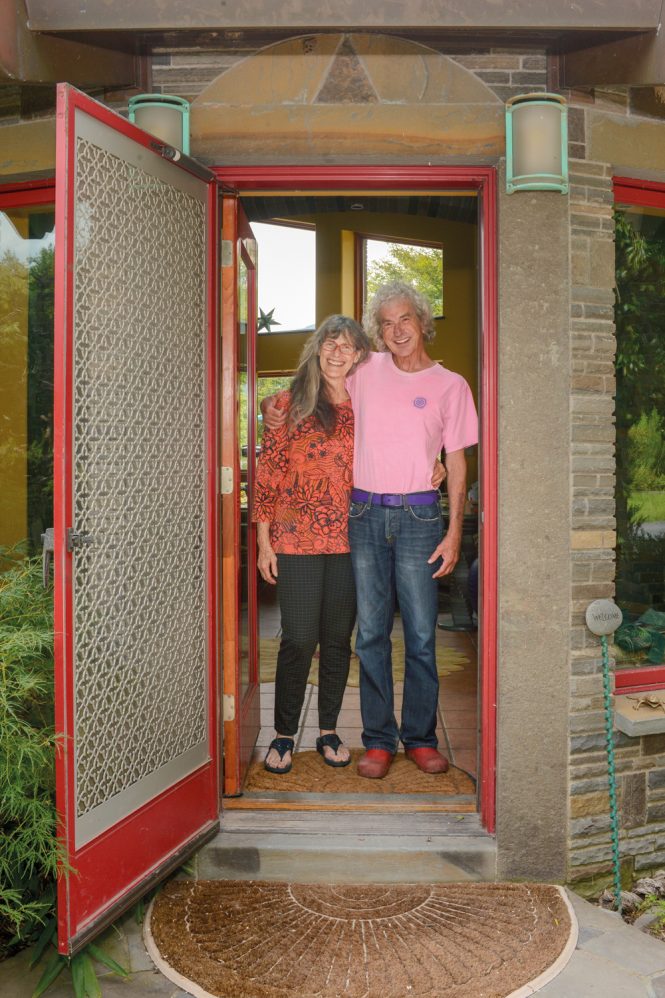

Guests enter on the eastern side, where four stories are visible. Over the front door is a bluestone arch with a keystone conforming to the proportions of the Fibonacci series—a sequence of numbers in which each number is the sum of the two preceding ones—and a carved yin-and-yang symbol. In the open first floor, the entryway flows into a sitting space; the living area, featuring a bluestone fireplace; the dining area; and the kitchen (with a half bathroom). The walls throughout the 2,000-square-foot top four floors are painted rich colors, like deep blue, golden ochre, and leafy green, and are decorated with Gottsleben’s brightly colored abstract paintings. His outdoor sculptures, made of bluestone and crystal glass, can be viewed from the many windows.

Livingston and Gottsleben stand in their entryway, beneath the keystone arch.

The building’s spiral core references the axis mundi, the mythical pillar connecting heaven and Earth. On the first floor, a three-quarter section of the stairwell has been cut away to reveal the staircase’s sculptural complexity as well as to allow access. On the first floor, the staircase is entered near the kitchen area. The 30-foot, highly polished stainless-steel, glass-stepped staircase, conceived by Gottsleben as a column of light, rises to the second floor, which holds the master bedroom, sitting area, and master bathroom; and the third floor, which houses Gottsleben’s study and a second full bathroom. A separate, stone staircase leads from the third floor to the observation room. Each floor is 50 percent smaller than the one below, based on the curve of the nautilus shell. (A separate, shorter spiral staircase also connects the first floor and the basement work area.) A built-in bookcase encircles the staircase, with the library organized upwards from books on practical matters to spiritual tomes. Outside of each floor is a balcony.

At the center of the house is the spiral staircase, rising inside the central column where the spiraling stone wall closes in on itself, and representing the axis mundi, or center pole of the world, of traditional sacred architecture.

At the top of the house, the observation room serves as the axis mundi’s “heaven,” with a load-bearing glass floor through which the stairwell, spiral staircase, and surrounding bookcase can be seen. The observation room’s windows offer views of Overlook Mountain and the rest of the Catskills.

The Spiral House was built to open the minds of everyone who enters it. As such, Gottsleben and Livingston’s grand-scale realization of their personal vision inspires readers to consider their own homes in new ways, perhaps finding ways to bring their own versions of the big picture to life. The Spiral House’s architecture, says Livingston, “expresses the idea that the house, in addition to all its usual functions, can be a place to inspire and inform the spirit.”

Seen through the observation room’s glass floor, Spiral House’s stairwell column carries light from the skylight all the way down to the basement.