Manitoga: A Beacon of Midcentury Modern Design

By Maria Ricapito | Photos by Vivian Linares | Fall 2019 | Features

Midcentury Modern has been making a comeback for the past two decades, and its minimal furnishings still look as fresh and innovative as they did during the postwar years, when the burgeoning American population adopted a more casual, egalitarian lifestyle. Today, Midcentury Modern designs are available from high-end sources like 1stdibs.com to low-end, big-box retailers. Designers and influencers hail Midcentury as so classic and versatile that it may be the only style that won’t ever go out of style.

The Midcentury Modern movement was led by industrial designer Russel Wright and his wife Mary, who established America’s first lifestyle brand, influencing future creators and tastemakers from Andy Warhol to Martha Stewart. Believing “good design is for everyone,” Wright rebelled against “style dictators” like Emily Post. Combining traditional and modern design and using durable, inexpensive materials, he created elegant, affordable functional objects for the layman.

Wright’s studio interior has been preserved just as he left it. Photo by Tara Wing.

Born into a Quaker family in 1904 in Lebanon, Ohio, Wright began studying architecture at Princeton but left to train with New York set designer Norman Bel Geddes, creator of the “Futurama” exhibit for the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

In the 1920s, Mary, the daughter of a textile manufacturer (and Albert Einstein’s niece), convinced her husband to turn his papier-mache animal props into metal bookends. They were a hit, and Wright soon switched from using chrome to cheaper, mass-marketable aluminum. His aluminum cocktail accessories proved so popular that they were featured in the Machine Art show at MoMA in 1934.

Michele Oka Doner’s burning star.

Wright is best known for his curvy-silhouetted, round-edged, richly-colored, mix-and-match dinnerware, made by Steubenville Pottery from 1939 to1959 (and currently produced by Bauer Pottery in Los Angeles). Created to be affordable, each piece of the American Modern line was imprinted on the back with Wright’s signature. The dinnerware line sold over 250 million pieces, and whenever new stock arrived at Macy’s, customers flocked there.

An array of other sleek, no-fuss, inexpensive home goods followed: serving sets, glassware, table and standing lamps, furniture made mostly of maple (which Wright called “the wood of our forefathers”), Bakelite radios, and a Wurlitzer organ.

Although Mary was also a designer, she became Wright’s marketing wiz. She exhibited his wares in lifelike rooms in department stores, which had never been done before; pioneered the concept of a design showroom; and brought theatricality to their presentations. In 1949, when Wright dumped a bin of new dishwasher-safe dinnerware on a metal table to demonstrate its durability, the New York Times reported that “even the most butter-fingered husband could be trusted to wash the Wrights’ casual china.” In 1950, the Wrights’ Guide to Easier Living was published, establishing them as design and lifestyle gurus. The book favored overthrowing tradition for modern ease, advising that, if, say, you couldn’t afford to throw a formal dinner party with grandma’s china, crystal, and silver, you could host a buffet instead—using Wright’s inexpensive, stylish tableware.

A display of Russel Wright-designed home products from the collection of George R. Kravis II.

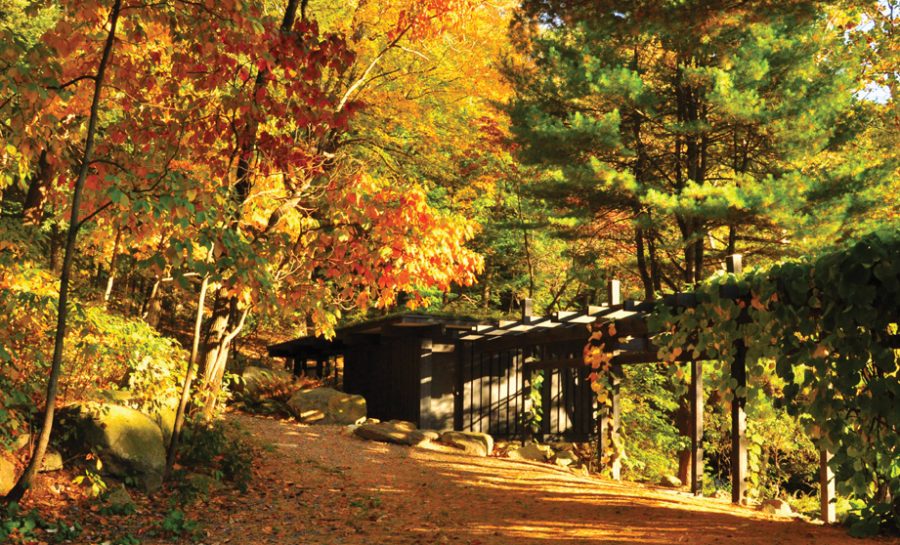

Although based in Manhattan, the Wrights also owned a property in Garrison, which can be toured today. Their upstate home was a lifestyle experiment, featured in Life magazine in 1962 as “A Wonderful House to Live In.”

The Wrights bought the 75-acre property, an abandoned granite quarry and logging site overlooking the Hudson River, in 1942. Wright spent 15 years studying its topography, creating trails, diverting a stream, planting native species, and turning the quarry into a swimming and skating pond with a 30-foot waterfall, while the couple lived in a small farmhouse (still existing). After Mary died of cancer, at age 47, in 1952, Wright hired architect David L. Leavitt to design a house on his chosen spot: a rock ledge overlooking the new pond. Wright designed the home’s interior while Leavitt did the exterior (though there is some controversy over who contributed what). Construction began in 1957; and in 1962, Wright moved in with his adopted daughter Ann, who named the house Dragon Rock, since its setting resembles a dragon curled around and sipping from the pond.

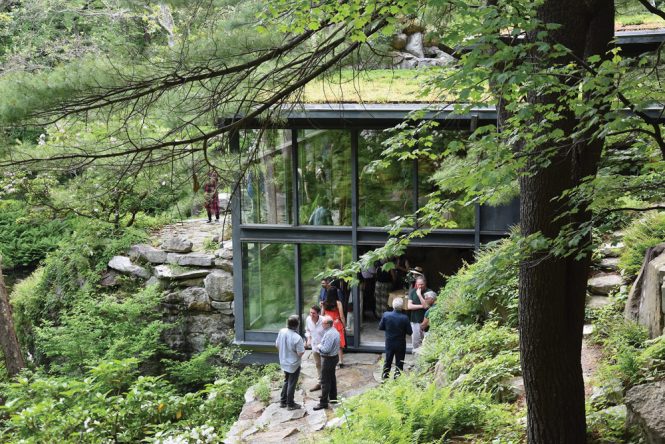

The 2019 opening celebration at Manitoga. Photo by Vivian Linares.

Today, the low-slung, Japanese-style house and museum is called Manitoga: The Russel Wright Design Center. Wright chose the Algonquin name, meaning “Place of the Great Spirit.” The property has been expanded to realize his full vision, featuring woodsy glades, moss “rooms,” wildflower-filled ravines, a grove of swaying birch trees Wright nicknamed “the Martha Graham Girls,” four miles of hiking paths (open year-round), and access to the Appalachian Trail.

“When [Wright] arrived, it was a scarred, desecrated landscape,” says Allison Cross, Manitoga’s executive director. “He brought it back to life.” The site, which offers tours of the house and studio from April to November, has more to offer than just Midcentury Modern design. It also teaches visitors about living in harmony with nature.

As a Manitoga artist-in-residence, Suzanne Thorpe rehearses with musicians for the commissioned work “Resonance and Resemblance,” which was performed from kayaks in the fall of 2017.

Wright delighted in the wilderness, designing the house to appear as if growing out of the stone, while keeping pieces of the site’s industrial past—metal rings drilled into the stone and bits of machinery for doorknobs. He brought nature indoors by “balancing modern materials—plastics and styrofoam, for example—with natural ones—granite with Formica or resin infused with pine needles or butterflies,” says Cross. The double-height living room is supported by a giant tree trunk. An early environmentalist, Wright created insulation from styrofoam, plastic laminate, and foil; included walls of windows designed for heating and cooling ; and built a “green” roof. The rooms have been preserved to showcase his lifestyle, down to a pack of Salem cigarettes in an ashtray on Wright’s desk—and tour guides demonstrate how the built-in shelving’s panels were swapped seasonally. A Saarinen dining table is set with American Modern.

A summertime lunch at Manitoga brings out some of Russel Wright’s vintage dishware.

“Manitoga represents a life dedicated to good design, which elevates the spirit and gives a sense of beauty and timelessness,” says Cross, who instituted an artist-in-residence program to help revitalize Manitoga. “One of the challenges of historic house museums, whether from the 1800s or the 20th century, is that we preserve them so you see that slice of time, but they have to stay alive,” she says. The residency program, which has hosted a dozen artist residents, is “about keeping alive and inspiring that spirit of creative output.” This fall, Ivy Baldwin Dance presents “Quarry,” a performance based on Wright’s desire to blur the line between inside and outside. Other programs are also under consideration, says Cross, including a design camp for adults, poet residencies, and retreats. A collection of over 500 Wright objects, from the late American industrial design collector George R. Kravis II, is being displayed.

A performance by Flamenco y Sol was part of the Palmas installation by artist Melissa McGill in 2014.

When it comes to design or sustainability, Manitoga offers “timeless lessons that were innovative in his day and they are very important for us to embrace because they are being ignored,” says Cross. “Ridiculously big houses or ones that pay no attention to the movement of the sun, so that they cost more to heat and cool, are being built. We’re repealing all kinds of environmental controls. It’s very important to hold up Manitoga as a beautiful oasis that has stood the test of time.”