Little House in the Big Woods

Jason Koxvold's Norwegian-Insired Compound in Napanoch

By Marie Doyon | Photos by Roy Gumpel | Fall 2018 | Features

As a child in the 1970s, photographer and creative director Jason Koxvold spent each summer roaming the forested mountains of Norway at his grandfather’s estate, Lidartunet. His grandfather, Leif Koxvold, founded the property in the 1950s after abruptly retiring to spend more time in nature, make paintings, and whittle gnomes and other fantastical figures. Over the next 20 years, the family added barns, houses, and outbuildings to create a bona fide family compound.

“Those 1800s Norwegian homes were just like Lincoln Logs,” Jason says. “My grandfather would drive around and find people selling their old houses, take them apart, then reassemble them onsite with my dad and uncle, and modernize them to ’70s standards—they’re pretty archaic again by now.” Lidartunet, which is still in the Koxvold family, has three main houses with plumbing and a dozen accessory structures, including an art studio, a blacksmith’s forge, barns, and a sauna.

“I grew up thinking that a place like Lidartunet was not unusual. We loved spending time there,” Jason says. After growing up in England, he moved to New York City, and while working full-time as an advertising creative director there in the late 2000s, found himself yearning for a sanctuary in nature—a place to recharge, experiment, and play—a place like Lidartunet. So, in 2008, he bought a 2.5-acre property in Napanoch in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains to create his own retreat. “The drive up from Rondout Reservoir reminded him of the drive up in Norway—all the trees,” says Jason’s wife Suzanne. “He really wanted a house in the woods. He didn’t even want a view.”

Koxvold’s plan was to build a modern interpretation of Lidartunet—indeed, he’s named his weekend home Lidar West (tunet means compound or courtyard and Lidar is the name of the mountain town in Norway). So he enlisted the help of his friend, San Francisco-based architect Alan Cross of Proto-inc. “I said, ‘Hey, Alan, do you think we can build a house for $100K?’” Jason recalls. “And he said, ‘Sounds pretty reasonable.’ It was stupid, but I was young.”

Jason Koxwold with his son Finn, for whom he plans to build a treehouse someday;

To the project, Jason brought not only the inspiration of his family compound, but also a love of modernist architecture, and a Dwell-inspired landscape sensibility. “In Dwell, people were always trying to build without disturbing the trees, saying things like, ‘Oh, we built on stilts because we didn’t want to harm any of the trees.’ I didn’t go that far, but I did try to leave as many as I could.”

Perched in a small clearing of red oaks and set slightly into the hill, the 1,400-square-foot house is geothermally heated and cooled. The east-facing front door opens into a hallway that divides the living area on the south side from the bedrooms on the east side. The open-plan kitchen-dining-sitting area is a spacious, white-walled room with oak floors; soaring 15-foot ceilings; and a floor-to-ceiling bank of windows on the west side, looking out onto the backyard.

The house’s cedar siding is set off by black trim around the windows and doors, accentuating its modernist vibe. Jason had originally envisioned a flat asphalt shingle roof, but after discovering that no manufacturer would guarantee that, he settled for the minimum pitch of 3:12. In the living area, the gently sloping ceiling seems to give way to the canopy of trees in the backyard beyond, an expansive sensation that transcends the indoor-outdoor divide.

Ash-gray cabinets line the kitchen wall, facing a Midcentury dining table and anchoring the airy, open-plan kitchen/dining/living space beneath a Noguchi light.

A tidy row of custom, ash-gray kitchen cabinets lines the south wall, anchoring the airy room. A Noguchi paper light fixture sits over a Midcentury dining table surrounded by Modernica chairs. Opposite, dark granite tile surrounds a built-in fireplace and wood storage nook, a nod to the Norwegian compound. On the same wall, an architectural bookshelf climbs nearly to the ceiling. “Jason wanted to have a lot of space for his books, so that was thought out from the beginning,” Suzanne says. “Some are art books. He loves to cook, so there are a lot of recipe books. He also has a lot of hobbies so there is ‘How to Keep Bees,’ ‘How to Build This and That.’ He is always starting some kind of new endeavor.”

At the other end of the house is a guest room-turned-nursery, for the Koxvolds’ two children—Finn and Summer, the master bedroom, with its own wall of west-facing windows, and, across the hall, a spacious bathroom. For the family, who lives mostly in an apartment in Prospect Heights, the ample kitchen and bathroom are elusive luxuries. “We really feel like we reset every weekend—we get to wake up and see backyard,” Suzanne says. “It’s nice how morning light comes in and gets broken up by blinds.”

A 15-foot bank of windows begins at the far wall opposite the kitchen area and near the fireplace, above which one of Jason’s paintings hangs.

A walnut stairway on the north end of the house leads down to the basement, which has another full bathroom for guests, a laundry area, a work studio for Jason, and a walk-out garage. The studio is a renaissance man’s creative lair. Chest freezers, all types of equipment, and tools line the walls, touting his diverse interests from woodworking to forestry to hunting.

The garage opens to the north side of house as well as to the backyard, where dappled sunlight filters through a dome-like canopy of trees. A toy excavator and a few brightly colored plastic balls adorn the Japanese rock garden Jason made. This is the best spot for taking in the home’s splendor: the impressive wall of windows, the stark black-stained cedar siding, and the geometric roof hip over the master bedroom, with all of it framed by lush green on every side.

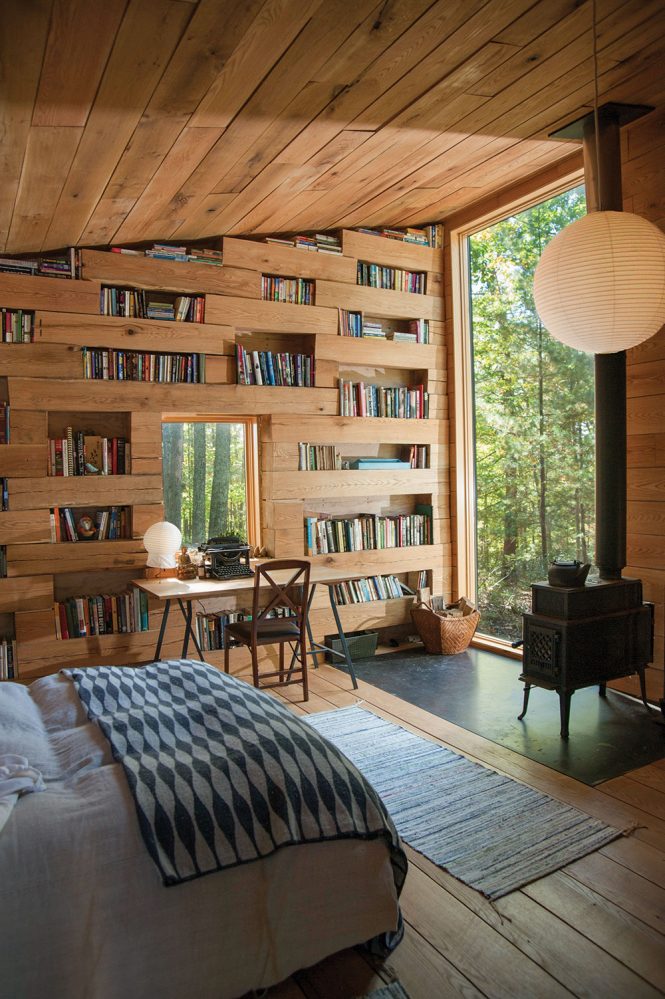

Lidar West is shaping up to be as whimsical and complex a compound as its predecessor, Lidartunet. Just across the lawn from the house, another dark modernist structure beckons—Hemmlig Rom, or “the secret library.” A tall, black cube with a single-pitch roof, it looks like a shard of volcanic glass. A 20-foot window is asymmetrically placed to give a view of nature without the main house.

“Having had my family from the UK visiting one Christmas, I realized that I needed a third bedroom,” Jason says. He shared his back-of-the-napkin sketches with his friend Brandon Padron, of Studio Padron, and the two collaborated to bring it to life. Architecturally, Hemmlig Rom is a standard stick-built structure, but inside, all four walls are lined by eight-inch oak beams, mostly harvested and milled onsite.

Hemmlig Rom, or “the secret library,” sits apart from the main house at the edge of the woods. It has electricity but no running water.

The beams are stacked at staggered intervals to create pockets of captured space, which are lined with over a thousand volumes. Jason freely admits to buying a lot of 2,000 books in bulk on Ebay to finish furnishing the place—a stop-gap until he can build out his own collection. “I have a lot of books—but not this many,” he says with a laugh. “The bottom shelves are mine, then as you get higher, it’s all Brenda Novak and Larry Bond: The Enemy Within. There are some terrible books up there.”

Hemmlig Rom, or “the secret library,” is a guest studio with a wood stove and a collection of 2,000 books lining the oak-beam shelves that run from floor to ceiling.

Jason plans to build a few more structures on the compound—a workshop, and when the kids are bigger, a treehouse. “It wasn’t until I got older that I realized how special Lidartunet is,” he says. “So I think a lot of what I’ve been doing is trying to give my children as wonderful a childhood as we had.”

Most weekends, the family drives to Napanoch on Friday evenings for a two-night stay. “This is my upstate,” says a contemplative, almost-three Finn, as he plays with his toy chainsaw. Sunday is a workday for Suzanne, who works with the real estate company Compass, so they usually head out early. But Jason, a freelancer, takes every opportunity to steal upstate on his own.

“He generally doesn’t have a nine-to-five, and he gets to work from home a lot. Sometimes he’ll say to me, ‘Oh, I have to get the mail. I’ve got to go upstate,’” Suzanne says with a knowing smile. “This is his happy place.”

Jason’s latest book, Knives, is a collection of documentary-style photographs of the closed Schrade knife factory in Ellenville