A Hudson Valley Architect Builds His Dream Home

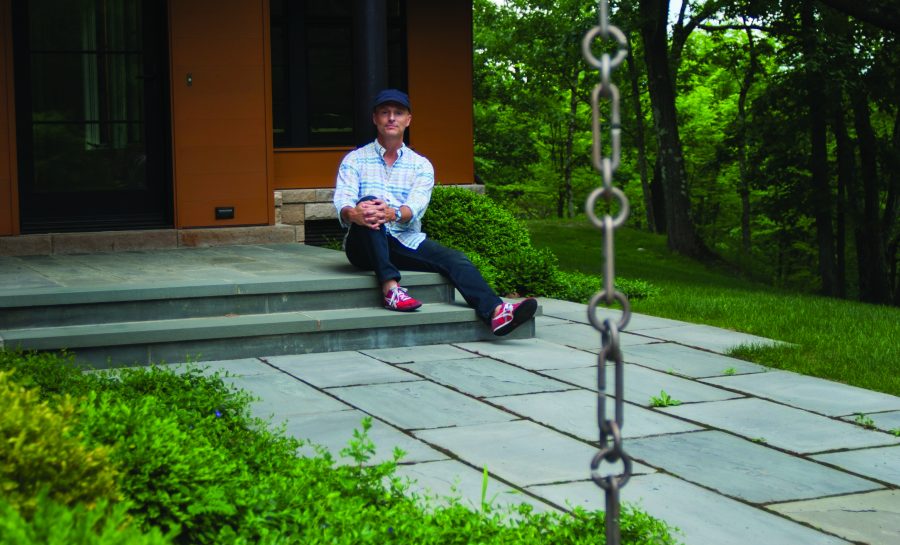

Steve Marchetti Builds a Modern Rustic Retreat [House Profile]

By Mary Angeles Armstrong | Roy Gumpel | Fall 2017 | Features

Shared Vision

Hudson Valley architect Steve Marchetti doesn’t live in his dream house, but he visits it often. Well-versed in traditional and modern vernaculars, he has enjoyed an easy rapport with clients over his 30-year career. But when one particular Manhattan couple asked him to design a weekend retreat in northern Dutchess County, Marchetti found them so remarkably simpatico with him that the resulting house, situated on a rolling hilltop, ultimately became his masterpiece—and the basis for a flourishing friendship. These days, his clients invite him over regularly for dinner, and ask him for guidance on furnishings or to tweak his original design to support their changing needs.

The fireplace is the centerpiece of the main section of the house, which Marchetti calls the “papa pavilion.”

A moss-covered hill slopes gently away from the house.

“Their vision corresponded exactly to what I would design for myself,” Marchetti recalls. His clients had just bought a ranch house on 16 acres outside Rhinebeck, but they envisioned creating a minimalist modern rustic house in its place. As a lifelong admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, Marchetti proposed employing Wright’s horizontally organized façades with a modern glass structure embowered in trees, and his clients loved the idea. “Usually I present six or seven different schemes to clients, but the first plan that came out of my head was exactly what they wanted,” he recalls. “It was bliss.”

Construction began in 2013 with the ranch house torn down and the new house sited in its former location, atop a long, winding driveway on the front third of the property. With the original house gone, Marchetti says, “There was no architectural context except to respond to nature.” The new house’s three interlocking rectangular pavilions create a complex form that sprawls over 150 feet from one end to the other, with the line of its façade flowing forward and back “like Norwegian fjords,” he says. It’s a nonhierarchical design, he explains, with “horizontal planes that don’t quite intersect, but rather lean and rest and pass each other.” Blocks of sandstone, sourced from Pennsylvania, ground the structure and create garden walls. Cedar siding helps the house blend in with the surrounding woods, and abundant glass reflects the greenery. Along the edge of the ballasted pebble roofline, weather-streaked copper trim is complemented by a Japanese rain chain.

The garage sits at the base of the southernmost pavilion.

The surrounding lawn slopes toward the woods and a moss-covered hill on one side and a stone terrace and pool in the back. A path of rectangular stones zigzags across the front lawn, past a large oak tree, to the house’s main entrance—simple steps leading to the central pavilion’s glass front door. Multiple alternative entrances create easy flow between indoors and out.

Pavilion with a Purpose

Each of the three pavilions in the 4,500-square-foot house has a distinct purpose, and is connected to the next by a gallery. Windows and glass walls let in views of the woods, creating a backdrop for the sleek, modernist interior design. When it came to the house’s interior, Marchetti and his clients discovered once again that they had an affinity. “They wanted a modern, comfortable feel with lots of clean lines,” he says. Rhinebeck’s Hundred Mile design showroom supplied colorful, whimsical furnishings, including a red “bouquet” chair and a metal-and-glass Pig Table by Moooi accompanied by two white plastic Jeanette-style dining chairs, designed by Edra, sporting backs that remind Marchetti of linguini.

Throughout the house are many whimsical touches like this metal-and-glass Pig Table by Moooi.

At the center is what Marchetti calls the “papa pavilion”—an open-plan space with an 18-foot ceiling that houses the living, dining, and kitchen areas. North- and west-facing windows and glass doors overlook the terrace and pool. The living area centers around a stone fireplace, crafted by Alfredo Masonry, with an exposed smokestack chimney; gray Santa Monica-style swivel armchairs by Poliform and a white couch border a silk-and-wool rug by CC Tapis that’s been faded to look antique.

The dining area features a wood-and-steel modern rustic dining table designed by Marchetti and constructed by furniture maker Todd Ossenfort. The kitchen is sleek, with white quartzite countertops, white lacquered cabinetry, and a stainless steel Subzero refrigerator framed by sealed cedar cabinets that match the exterior of the house. Black-and-white Granada tiles form the backsplash for the stainless-steel Wolf stove and the kickplate of the dining counter, which is lined with blue stools.

The sleek white kitchen centers around a Wolf stove and quartzite-topped dining island, both tiled with eye-catching black-and-white Granada tiles.

On the ground floor of the southernmost pavilion are a mudroom, accessible from the garage and living room, and a three-season porch leading to the terrace. The upstairs guest area is reached from the living area via a floating steel staircase. Marchetti secured the treads with a steel beam extended along the wall of glass doors to make the steps look as if they are “the branches of a steel tree,” he says.

Upstairs

At the top is a library leading to three bedrooms and a shared bath with a penny-tile floor. Two of the bedrooms feature picture portholes and gridded rectangular windows. A third, larger bedroom has three walls of windows and is furnished with a ’50s-style leather chair by Room & Board and a low blue dresser.

A floating steel staircase leads from the living area in the “papa pavilion” to the library and guest wing.

The northernmost pavilion comprises the master wing, which features a study, dressing room, and master bath. The entrance to this wing features a sliding, soundproof panel, providing complete privacy; the entrance opens to a study equipped with a long, built-in desk, which in turn leads to a dressing area and the bedroom. The master bathroom, with a porthole window, is situated on the far side of the bedroom. The bed, also designed by Marchetti and built by Ossenfort, features shelving concealed by panels, and sits beneath a pop-up roof inset with windows.

Because the master bedroom’s windows face in all four directions, Marchetti has dubbed this pavilion “the lighthouse.” From the bedroom, the views of the sky and woods encapsulate the sense of tranquility that his clients wanted—and emulate the vision of Frank Lloyd Wright. “It’s as if we are lifted up from the earth by the forest,” Marchetti says, “on top of a wave of trees.”

In this issue we’re also profile the live-work space of artists Neville Bean and Harris Diamant.