Estate of Bliss

A Dressed-Up Farmhouse in Claryville, NY

By Mary Angeles Armstrong | Photos by Deborah DeGraffenreid | Spring 2020 | Features | House Feature

Ensconced in busy lives in Brooklyn, Nestor Sulikowski and Paula Madrid nonetheless couldn’t forget the happy childhoods they had spent among the mountains of South America. Sulikowski hails from the Argentine city of Cordoba, nestled amidst the Sierras Chicas, while Madrid was raised in Medellin, Colombia, amid an extended family that included 23 cousins and multiple aunts and uncles with property in the Andes.

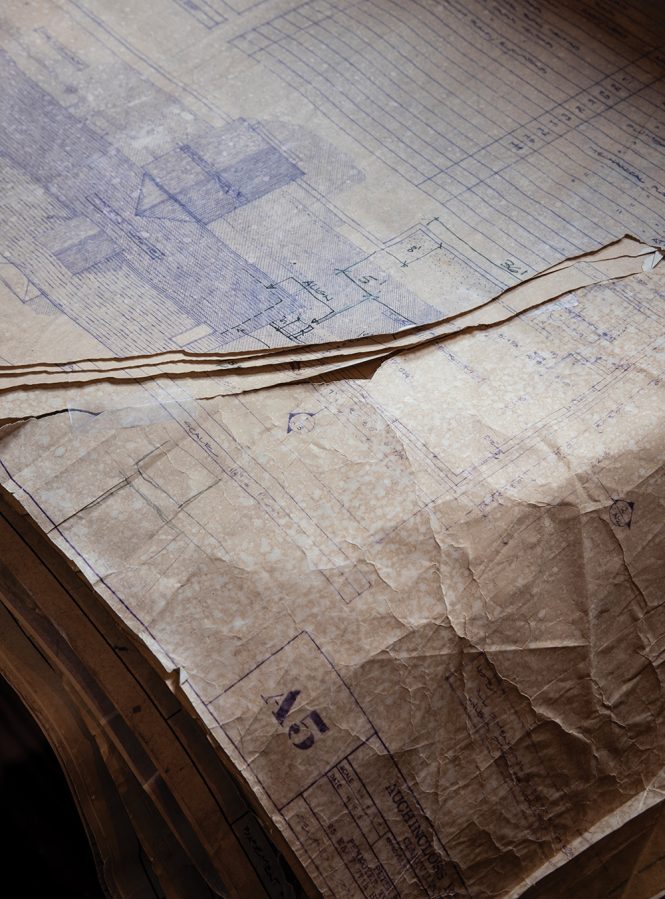

Architect Peter Pennoyer’s original plans for Catskill Park Manor, which the late New York City writer Louis Auchincloss and his artist wife Adele commissioned.

“One uncle had a big truck with an open back,” recalls Madrid, a forensic and clinical psychologist. “He would go around town, picking up all the cousins. Then we’d choose our destination. Wherever we chose, we spent a great deal of time running around, horseback riding, and hiding in the forest.”

Adele Auchincloss’s former art studio, located over the porte cochere, is now a den and playroom featuring colorful furnishings.

Madrid and Sulikowski, a bond trader, wanted their daughter Chloe, now seven, to grow up as they had: enjoying nature, surrounded by mountains, and sharing that experience with her friends. So the couple decided to look for a house in the Catskills. “We went looking for the green and the scenery,” says Sulikowski. But beyond that, he admits, “We didn’t quite know what we were looking for.”

Nonetheless, the family struck gold: Catskill Park Manor, a 3,749-square-foot, three-story neoclassical masterpiece, inspired by early-20th-century Swedish architecture, perched on a steep hillside outside Claryville in Sullivan County—“a farmhouse that’s been dressed up a bit,” according to its Manhattan-based architect, Peter Pennoyer.

The house was built in 1992 by the late lawyer and novelist Louis Auchincloss, whose 50-some books chronicled the lives of upper-class New Yorkers, and his wife Adele, a painter and environmentalist who chose the site and designed the native landscaping. Originally surrounded by 400 acres, the house now sits among 131 acres of woods on a hillside and inlet between the Neversink River’s east and west branches; the remaining original acreage, stretching across Wildcat Mountain, is state-designated forever wild land. “I hope it doesn’t sound corny to say, but it really clicked, maybe because of both of our pasts surrounded by mountains,” says Sulikowski.

The sunny living area features a fireplace and original artwork by Madrid and Sulikowski, and opens onto a porch and garden.

Pennoyer was just starting out when he was hired by the Auchinclosses to design their weekend escape from New York City. Now the head of a 50-person, award-winning design firm specializing in traditional and classic architecture, Pennoyer says the project launched his career. “I was a great admirer of Mr. Auchincloss and his writing,” he says. “It was a risk to have a young architect design their house. It took courage, and I am eternally grateful that [Louis] and Adele had confidence in me.”

Pennoyer worked with Adele Auchincloss to develop the four-bedroom, 3.5-bath house’s design. “She had specific ideas about what would make the house a comfortable place for her and her husband,” he says. “Louis needed a library and a place to write, but didn’t want to be sequestered away in a closed room, and she wanted a studio for her art.”

Louis Auchincloss’s intact original library sits at the center of the house within a two-story rotunda and beneath a third-floor oculus.

The house centers on a two-story rotunda that stands open between the first and second floors and is topped with a third-floor, pop-out oculus with south-facing windows—all designed to capitalize on the views and allow for the maximum amount of light and circulation of heat during winter.

The Nordic architectural vernacular known as Swedish Grace inspired the exterior design. “It’s a style of architecture and decorative arts that’s fundamentally very honest,” explains Pennoyer. “It informs humbled structures that are almost barnlike, but with elements that refer to the traditional and classicalism.” The style is best exemplified by Eric Gunnar Asplund’s Villa Snellman, an early 20th-century house outside Stockholm with a simplified rectangular structure given ornate flourishes.

The spacious, eat-in kitchen features a small pantry and French doors leading to the backyard.

Along the south-facing exterior wall are rows of rectangular windows featuring copper swags and moldings. “They are small, light touches of traditional ornament,” says Pennoyer. Above the rectangular windows, he notes, arched windows “suggest that there’s a grander space behind.”

The house is situated at the top of a long, curving driveway that ends with an ivy-covered porte cochere, or covered entrance, extending from the house’s northern side into the mountain. “If someone arrives in the middle of a snowstorm, they have cover while entering the house,” says Pennoyer.

The house is barnlike, inspired by a Nordic architectural style called Swedish Grace that is “fundamentally very honest” and “almost barnlike,” but with classical elements, says Pennoyer.

Adele Auchincloss’s former art studio, located over the porte cochere and boasting windows on three sides, is now a den and playroom, repainted teal green and decorated with colorful Moroccan fabric-covered chairs from Beam Brooklyn. The room can be accessed inside from the second floor hallway or via an outside door on its northern end, allowing the space to function as a bridge between the house and the hill behind. “So if you want to take a walk, and you’re inside the house, you could actually do so from the second floor, which is an unusual feature,” says Pennoyer.

Steps lead down from the porte cochere into a spacious, wood-paneled mudroom with ample room for coats, hats, and boots. The central rotunda sits opposite the main entrance, and houses Auchincloss’s circular writing room. Featuring several south-facing windows, and open to the second-floor library and the third-floor oculus, the space was designed to be flooded with light. The view, says Pennoyer, is centered on “a distant break between two mountains in the Catskill range. The room’s location is directly related to the view of that focal point of the distant in the horizon.”

The second-floor library, whose rows of bookshelves line either side of the rotunda, remains filled with Auchincloss’s extensive collection of reference books on gardening, the local landscape, and classic fiction. Sulikowski and Madrid have added copies of Auchincloss’s own fiction and essays.

The writing studio has been turned into a formal dining room centered on a round wooden table with seating for 12. Next door, the spacious, teal-painted, eat-in kitchen features French doors, a small pantry, a closet, and open shelving.

Between the entryway and dining room, a wood-paneled hallway runs along the building’s entire east-west axis, widening gradually toward the western end. “I wanted to introduce a dynamic feeling that draws people into the living room at the end of the house,” explains Pennoyer. Steps lead down into the cozy living room, whose wood-paneled walls have been painted white with mint green trim. There are high, green, arched ceilings; a brick fireplace; a pass-through window to the adjacent kitchen; and three sets of west-facing French doors leading to a covered porch bordered by a deck and raised-bed vegetable garden.

At the hallway’s east end is the master bedroom suite, featuring wood-paneled walls; French windows overlooking the lawn and woods; and a white-tiled bathroom. Sulikowski and Madrid have added an iron-framed bed and antique iron curtain rods to enhance the room’s rustic character.

The exterior features rows of rectangular windows; above many of the windows are copper swags, traditional Swedish ornaments.

The main staircase rises from the hallway, encircles the rotunda, and leads to the second-floor hallway and three wood-paneled bedrooms, each featuring sloped ceilings and outfitted with iron-framed beds. The bedrooms are decorated with Sulikowski and Madrid’s own modernist acrylic paintings—a vocation they share and explore on weekends at the house.

So far, say Sulikowski and Madrid, their attempt to introduce Chloe to country life has been a great success. “She’s created many rituals at the house,” Madrid notes. “She’s learned about trees, flowers, and animals, and she’s named our vegetable garden the ‘garden of happiness.’”

In addition to their many outdoor activities, the family spends time each weekend in the library, losing themselves in Auchincloss’s books. “We often find ourselves picking one out and reading about something we’ve never heard about,” says Madrid. “We love the architecture. We love the books. The history is a big part of the house.”