Artists’ Oasis

A Creative Couple Builds A Hudson Home and Studios for Aging in Place

By Niva Dorell | Fall 2020 | Design Feature | Features | House FeatureOn one of Hudson’s oldest streets, Margaret Saliske and Anthony Thompson’s house stands tall and far back, behind a fence with a gate covered in clematis vines. The H-shaped, charcoal gray house was designed by architect Grigori Fateyev to be unobtrusive. At night, with the lights off, it disappears almost completely into the dark, but on a sunny day, the sharp-edged, concrete house manages to blend in with, yet stand out among, the surrounding Victorian, Georgian, and Tudor houses.

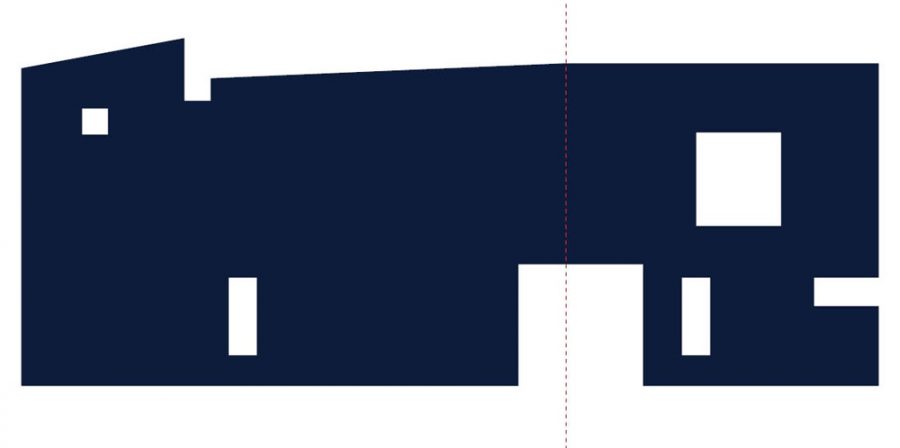

The building is both an art studio and dwelling for its owners, Saliske, a sculptor, and Thompson, an abstract landscape painter. After over 20 years of restoring the 5,000-square-foot, 19th-century Greek Revival house next door, where they raised their daughter and cared for Saliske’s elderly mother, the artists sold their former home and half of the original 1.25-acre plot to build a new house for growing old together on the remaining half of the property.

Saliske and Thompson’s chance introduction in 2010 to Fateyev, principal of Hillsdale-based Art Forms Architecture, through their mutual friend, the astrologer A.T. Mann, led to a collaboration with clear parameters. Saliske and Thompson each wanted their own independently functional studio building—standing side by side to form the two parallel lines of the letter H—that would be joined together by a common space—the H’s horizontal middle line; the house also needed to include a handicapped-accessible bathroom and a patio for outdoor dining. Caring for Saliske’s mother influenced their approach to designing a space to accommodate their later years: Saliske is 66 and Thompson is 82. “How you stay in your house when you get older was important to us,” Saliske recalls. “You can’t stay in your home if you can’t get in the shower.”

The design process began with the couple showing rough sketches of their ideas to Fateyev, who grew up in St. Petersburg, Russia, and designs art studios, galleries, and museums—“spaces for making art, and spaces for contextualizing, framing, and exhibiting it,” he says. “I see artists as important colleagues, because they are doing research into questions of spatiality and space, and of course, questioning the human condition, which we [architects] are also doing.”

Once the master plan was complete, and community opposition to building a contemporary structure in a historic district was overcome, Thompson’s side of the building was constructed first, and the couple lived there while Saliske’s side was built. “It was great to have him go first,” says Saliske, who had extra time to tweak her design. The entire 2,400-square-foot building, including both studios and the connecting common space, was completed in 2015.

“I think artists spend a lot of time imagining their ideal studio,” says Thompson. “Most people never realize it, but we were really lucky. We had ideas, and Grigori made them functional and made them real.”

Fateyev built the house using insulating concrete forms, triple-layered insulated glass, radiant concrete floors, and fiberglass window frames to create an airtight house that nearly meets the passive standard. The couple’s heat and electric bill is 20 percent of the cost of heating their old house in winter.

Since poured concrete becomes a structural element—the walls support themselves—Fateyev was able to create cutaway windows and entrances. Also, with concrete, Fateyev notes, there is less rotting, mold, and mice, which were problems in the Greek Revival.

“You think as an artist you can design your own space, but you really can’t,” Saliske says. “You think that you really know how you want to move through a space, but you don’t understand proportions in relation to yourself all that well. I’m continually so pleased as to how my physical being works in the space—how wide, how high, what the distances are—and it’s so hard for someone who’s not an architect to realize that, even though you’re a visual person.”

The artists, who often visit each other during the day, meet for a cup of tea in Thompson’s studio. Photo by Melanie Basner.

Thompson wanted a building with indirect sunlight from above, as much windowless wall space as possible, and a distance of 36 feet from the farthest wall—the optimal distance from which to view his artwork. “That distance didn’t have to necessarily be part of his painting space, just a point at which Tony could view his work,” Fateyev recalls.

Thompson’s large, cube-shaped studio is entered via a kitchenette (one cabinet for dishes, the rest for art supplies) through an eight-foot glass door with an exterior “screen door” of wood slats. Fateyev calculated that skinny north-facing skylights in the 22-foot ceiling would provide the greatest amount of indirect sunlight, so he installed seven two-by-six-foot Velux skylights to filter the light and insulate the room. In the middle of summer, the skylights let in shafts of sunlight; the rest of the year, they allow only indirect light, yet the room remains bright. Being in Thompson’s studio, says Saliske, is “like being in a shoe box with the lid off. It’s an atmosphere of perfect light.”

A second-floor loft serves as a storage space for Thompson’s paintings and a guest bedroom, with sanded, sealed plyboard floors that are easy to clean. The bed, with a 36-inch-high guardrail wall behind it, overlooks the studio. On the opposite south-facing wall is a five-by-six-foot window offering views of Olana and Mount Merino on clear winter days. Thompson’s space also contains a full bathroom and a mechanical room.

The single-story, 400-square-foot common space, which the couple nicknamed the “DMZ”—demilitarized zone—between the two studios, contains the kitchen and dining area. A north-side outlet to the backyard provides a view of the couple’s old house. Sliding doors on the south side lead to the front yard and a terrace, where Saliske and Thompson dine in the warmer months, gazing over a boxwood hedge at a profusion of perennial flowers and trees, including a Japanese maple, spirea, mock orange, red obelisk beech, ilex, red sunset maple, Japanese lilac, river birch, smoke bush, and Chinese junipers.

For her building, Saliske wanted lots of direct sunlight. “I want to feel like I’m living outside and inside at the same time,” she told Fateyev. Since she also does antique restoration and conservation—her commissions include Olana’s interior decorative stencils and a decorative wall painting at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site—she also wanted a wood workshop, a door wide enough to fit furniture, and more windows.

Fateyev designed Saliske’s building using a general 20-by-20-foot cube as a starting point. Her studio is entered through the DMZ via a 24-inch doorway encased in 10-inch-thick concrete walls. The relative narrowness of this entry, Fateyev explains, emphasizes the intentionality of the passage, making going into Saliske’s high-ceilinged studio feel deliberate and uplifting, like entering a sacred space.

To achieve Saliske’s “outside/inside” feeling, Fateyev created a 16-foot glass curtain wall of six windows wrapping around a corner. A four-foot-wide glass door provides additional access to the outdoors and lets Saliske bring in materials; above is a four-by-four-foot Velux accent skylight.

The couple’s dog often sits by the windows, watching the birds outside, and Saliske says when she brings her potted plants inside for winter, her studio feels like a jungle. There are woodcutting and polishing machines; and adjacent are a laundry nook and large, white subway-tiled, handicapped-accessible bathroom with glass shower wall.

Bamboo stairs lead to a living area, positioned over Saliske’s studio, including a couch, armchairs, and a TV nestled into bookshelves covering a wall. A small writing desk sits beneath a window. A double sliding door separates the living area from Saliske’s bedroom and bathroom, which features a small skylight. The disappearing sliding doors and glass guardrail wall overlooking the studio provide an unobstructed view from the bedroom into the living area and the studio’s massive windows below. An almost imperceptible incline in the ceiling (two inches per foot) allows for water drainage without gutters.

The loft on Saliske’s side of the house doubles as an office and living area. Photo by Dan Karp.

Typically, the couple dines and spends evenings together, but during the day, they live in their separate spaces. “We love to visit each other,” Saliske says. “We’ll have lunch in my space and tea in his space. We’ll go in and look at each other’s work and hang out in each other’s spaces. It’s really nice.”

While both sides of the building are entered at ground level, only Saliske’s bathroom is fully handicapped accessible. “The plan,” she says, “is that we would eventually reside in my space with Tony’s space being rented.” Her stairway will allow a chair lift to be installed.

For Fateyev, Saliske and Thompson being artists was advantageous because they paid extra attention to aesthetic details like the exterior paint color (Evening Dove by Benjamin Moore) and the wood treatment at the back of the house, which Saliske stained. Saliske also designed the dining area’s loveseat, Thompson’s cabinet, and several chairs. However, without an official living room, there’s not much need for furniture; in fact, when a friend asked Saliske, “Where do you entertain?” she laughingly replied, “We don’t entertain.”

Saliske and Thompson found the process of working with Fateyev delightful. “It wasn’t like that David Byrne song, ‘This is not my beautiful house,’” Saliske laughs. “Grigori was so much fun to work with because he had no ego. He was willing to try anything.” While Fateyev “created spaces around our needs,” she adds, “as much as I knew what I needed, I could never have imagined that space, and it continues to surprise me.”